The Conversation that Must be Had

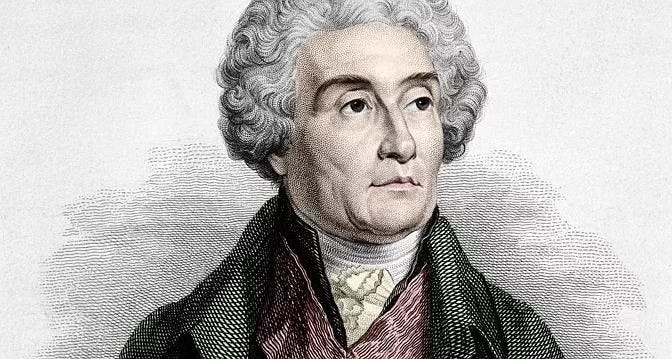

In his essay, ‘The Generative Principle of Political Constitutions’, 18th century philosopher, diplomat, magistrate, and forefather of conservatism, Joseph de Maistre makes the following and very important point:

“Man cannot make a constitution, and no legitimate constitution can be written… the corpus of fundamental laws that must constitute a civil or religious society have never been and never will be written. This can be done only when the society is already constituted…”

In his 2024 book ‘The Total State: How Liberal Democracies Become Tyrannies’, Auron Macintyre elaborates on de Maistre’s point:

“De Maistre believes that constitutions do not by themselves create the cultural norms, laws, and institutions that rule over a people. Instead, they simply formalize those that have already arisen naturally out of the character of the people. The true meaning of laws and constitutions cannot be captured on paper because the true meaning exists in the context of the people and the society that created them. They can only be truly understood in the lived experience of the culture from which they were naturally derived. It is the common nature of the people, the shared frame of reference, that creates the actual meaning of laws and constitutions.”1

In other words; constitutions (and treaties) are not top down external mechanisms for social and political control of a people. They are a formalised written expression of a reality that is embodied and lived at the grassroots of a nation.

Echoing another point made by de Maistre, Macintyre warns that:

“Relying too heavily on a written constitution simply incentivises a nation’s leaders to become skilled at twisting and shaping language in order to circumvent the restrictions created by the formal meaning of its words.”2

I couldn’t help but be reminded of these profoundly important truths as the public reaction to the Treaty Principles Bill has intensified both inside and outside of the New Zealand Parliament over the past few days.

To make matters more challenging, this spiralling intensity is also being fuelled by a particular ideological lens of our present age, identity politics, and the growing political divide of this era between the ruling elites and those on the receiving end of their dictates.

As Patrick Deneen succinctly puts it:

“…through its invocation of “identity politics,” the contemporary ruling class uses power not in a traditionally forthright manner, but through a recourse to a weaponised form of John Stuart Mill’s “harm principle,” in which perceived slights to identity are used as aggressive tools of control and domination. Particularly through claims of victimisation by those occupying (or preparing to occupy) positions of power and influence, the ruling elite seeks to limit and even oppress or extirpate remnants of traditional belief and practice—those especially informing the worldview of the working class—while claiming that these views are those of the oppressors.”3

In a nutshell; a significant and growing number of New Zealanders feel that something is amiss with the current interpretation and practical application of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Or, put another way; there is an important question of national identity and societal structure - a tension which has been simmering away for some years now, which has finally erupted into the realm of possible concrete political resolution through the Parliamentary process - but which the ruling elites are desperately trying to suppress, often with cries of ‘racism!’

Just consider the absurdity of a National Government which has supported the Treaty Principles Bill at the first reading, and into the select committee stage, but which has already declared that - irregardless of what the NZ people say to their elected representatives during the upcoming submissions process - they will be voting against the bill at the next reading to ensure its demise.

This is beyond the usual contempt that New Zealanders have long grown accustomed to from successive Governments who have ignored the overwhelming public voice in submissions on other previous bills - Jacinda Ardern’s extreme abortion law being just one recent example.

What we are now witnessing is an elite ruling class that is openly declaring that it has no intention of even listening to the people before the people have even had their chance to open their mouths and express themselves about a fundamental matter of nationhood.

The Government has brazenly declared that what is about to unfold is a meaningless charade - a vacuous pretence of open governance - because they intend to enact their will upon the people even if that is not what the people want.

I don’t think it would be unreasonable to suggest that the potential demoralising effect this approach could have (even well beyond this bill), on our normative method of inviting and listening to the voice of citizens in the act of lawmaking, could even be described as a deliberate corrupting of the democratic process.

This isn’t just a problem of our nation’s deeply held beliefs about the practical application of the Treaty of Waitangi, it’s now become a very open expression of contempt from the ruling classes for those they are elected to serve.

What National is doing is going to be far worse for our nation than addressing this matter with wisdom and competent leadership by facilitating a peaceful and robust public dialogue about the question of how the Treaty should be understood and lived by our people.

Joseph de Maistre was right. A constitution, or, in this case, a treaty, is only as meaningful and real as that which is believed and lived by the people.

If the people don’t view a treaty in the same way that the elites do, or they believe it is being misinterpreted, there is a serious foundational issue which wise and prudent leaders would recognise as being in need of urgent resolution.

Refusing to address this matter won’t bring this deep underlying crisis to an end.

Most New Zealanders seeking a resolution to Treaty questions are not racists, they simply no longer feel that the current official approach to the Treaty of Waitangi is a just one.

They could be wrong, but simply treating 46% of the population as if they are, by refusing to take their engagement with their elected representatives seriously, or accusing them of racism, is not good governance, it is a recipe for disaster.

This is a public conversation that a wise and prudent government would recognise must be had, no matter how challenging they might find such a responsibility, lest future generations inherit the burden of a nation deeply divided along racial fault lines.

Because the one thing that New Zealanders are now well aware of is that hidden fault lines have the propensity to explode in sudden and very frightening and destructive ways.

Macintyre, Auron . The Total State: How Liberal Democracies Become Tyrannies (p. 56). Skyhorse Publishing.

Macintyre, Auron . The Total State: How Liberal Democracies Become Tyrannies (p. 57). Skyhorse Publishing.

Deneen, Patrick. Regime Change: Towards a Postliberal Future (p. 41). Forum.

Very clearly and intelligently expressed thank you. It's not rocket science. What an embarrassment it all is.